P2P Research Study Findings

The SURVEY and FOCUS GROUPS data are presented below followed by summary remarks and recommendations for the next iteration of P2P.

Survey Results

Introduction

The 20-question online survey (Appendix B) of participants was conducted after the conclusion of the P2P program. The survey questions were a mix of quantitative and qualitative. All P2P Program registrants were invited to participate. Of the 32 P2P Program participants 23 participated in the survey: 12 mentors and 11 mentees for a response rate of 72%. What follows is a summation of those responses.

Recruitment Communication

Participants were contacted by email, webinar, newsletter or word of mouth and the program was on the CTSI website. In answering How did you first learn about the P2P program?, 16 participants wrote that they learned about the program through email or the CTSI newsletter, four from word of mouth, two from the CTSI website and one from a personal email.

Motivation to Participate

Participants answers to a question What motivated you to participate in the Program? included wanting to develop mentorship skills, connect with others, build a network, learn new or specific teaching strategies such as large classroom student interaction or online strategies, benefit from career development guidance, and to experience a meaningful mentor-mentee relationship.

Partner Meetings

The participants met throughout the pilot period in person, with some supplemental or substitute meetings via phone, email or Skype. They typically met in offices, other spaces on campus or coffee shops. Meetings were an average of 51 minutes in length with a range of 30 to 60 minute meetings and one respondent who had a pre-existing work relationship with their partner and worked very close by had many 15-minute meetings. The frequency of the respondents’ meetings was variable from weekly to only three times within the term. Five respondents reported meeting every week and 6 reported 1 meeting per month or less. The others met every 2-3 weeks or described their meeting frequency as variable or sporadic.

Facilitators and Barriers to Meeting

Time was reported as the biggest barrier to meeting with 13% respondents citing this in their qualitative survey response to the question What facilitators or barriers either supported or hindered meeting with your partner? For four participants, illness or another unexpected life event interfered with regular meetings. Factors that supported meetings included: the structure of the program, having made a routine or commitment to regularly meeting, being in close proximity on campus, perceiving that the program offered flexibility in meeting frequency and meeting length and exercising that flexibility, and the coffee card, provided by CTSI for P2P participants.

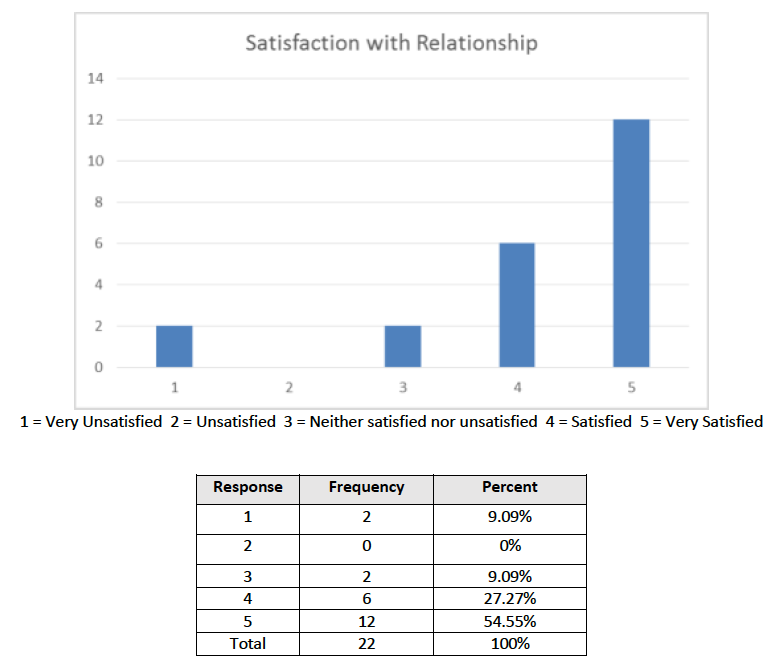

Relationship

Participants rated their overall satisfaction with their mentee-mentor relationship (Overall, how satisfied were you with your P2P partner relationship?) as “very unsatisfied” (1), “unsatisfied” (2), “neither satisfied or nor unsatisfied” (3), “satisfied” (4) or “very satisfied” (5). Both mentees and mentors ratings were an average of 4.18 out on this 5.0 point scale. This concurs with the qualitative survey data of high levels of satisfaction with the mentorship experience.

In answering Please describe the quality of your relationship with your P2P partner and elaborate on the reasons why, all but two survey respondents (90%) included comments such as “good rapport” or “fit” or “respect” in their description of the quality of their mentor-mentee relationship. They found they had compatible goals, values or interests. The majority of the time being from different disciplines was reported as positive. However, one pairing was not by similar stream (e.g. a tenure stream instructor was paired with a teaching stream instructor) and this was reported as a challenge. The one participant who selected “very unsatisfied” with their relationship had indicated a very positive experience in their other answers. It is possible this was a mis-chosen selection as “very satisfied” would be more in keeping with their other answers.

Nineteen out of 21 survey respondents stated that they would like to meet with their partner in the future with 13 replying that they had already met since the conclusion of the program and 19 responding that they had plans to meet.

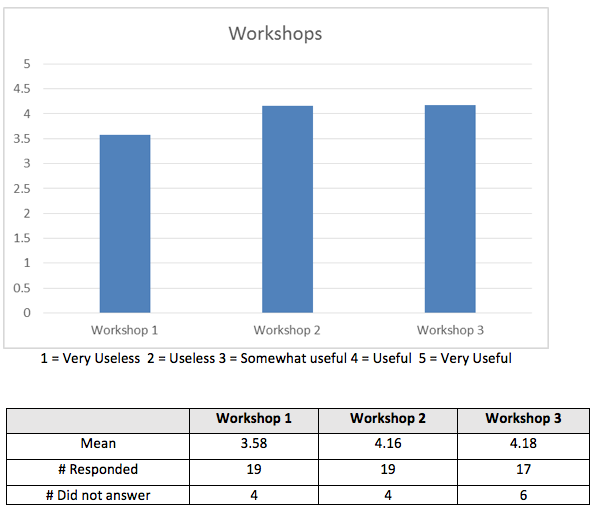

Programming – Workshops

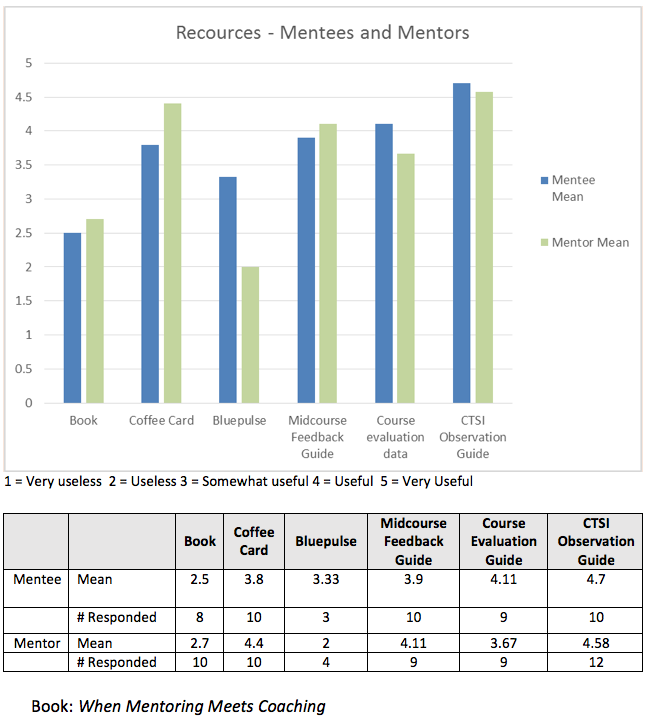

There is a correspondence between scores on resources and the accompanying resources (below). Workshop #1 was the least highly ranked, as was the resource book introduced in Workshop #1.

The CTSI Peer Observation of Teaching: Effective Practices guide and coffee card received the highest ratings, and the published resource book When Mentoring Meets Coaching, and Bluepulse the lowest.

Mentor vs Mentee Scores

Mentors and Mentees scored satisfaction with their mentor-coach relationship identically but there were two differences in scoring that are of interest. The coffee card was scored higher by mentors than mentees (4.4 vs 3.8) and the course evaluation data were given a slightly higher score by mentees than mentors (4.11 vs 3.67).

Broad Benefits

The success of the P2P program was articulated in a qualitative question: Please describe any broad benefits you feel you gained through participation in the program. Participants reported gaining connection, expanding their network, learning and trying new teaching strategies, developing mentoring skills and new listening skills, feeling re-energized in their teaching, learning more about the university and about peer mentoring for teaching at U of T, and feeling optimistic about the future of mentoring at U of T. For example, representative quotes include:

“I have developed a very positive relationship with a teaching faculty member from a different faculty to my own. Our sharing of ideas has given me much food for thought regarding the way in which mentorship could be broadened out in my own department and how feedback could be solicited from students in our large courses.”

“Overall, participation in this program has enabled me to renew my love of teaching.”

“(Participation) lead to a greater understanding of the university”

“Revitalized my motivation and belief in peers’ interests in teaching development. Helped me frame and work on my own teaching.”

When asked if they would recommend the program to others (If there are future iterations of this program, will you recommend it to others? Yes, No, Comments), 100% replied yes. “Loved it.” “Absolutely” “Programs like this are vital to developing a teaching community at U of T.”

Importantly,

18 out of 22 respondents replied that they would like to be involved in the program again.

Focus Group Findings

Eleven mentors and nine mentees participated in the focus groups. Dominant themes are presented below in three sections: program elements and structure, resources and activities, and mentor-mentee relationships and conversations.

Program Elements and Structure

Time requirements. The time requirements of the program were reported as greater than expected but those who met with their partner regularly and participated fully reported that they found it rewarding. Time was the most frequently cited barrier or challenge to participation and it was recommended that people be aware going into the program of what would be required. Several participants expressed interest in their department Chairs fully understanding the extent to which they were committed and involved. The considerable commitment, however, was also cited as contributing to the value and effectiveness of the program.

“I thought ‘oh my God, an hour every week, how will I find that time?’ And I did, but it’s a lot.”

“We actually met quite a lot…over a dozen times in person.”

“I was happy with the time because it actually made me feel like I have a commitment to this program…I took pride in the fact that we took all this time to do this.”

“Scheduling was a challenge.”

Some participants saw flexibility as an inherent benefit of the P2P program and arranged their meeting times, locations and meeting lengths to suit their needs.

“We didn’t follow the rules. We couldn’t meet every week – I teach 8 hours a day for three months…It was tricky.”

“You know, none of us followed the rules and yet the whole thing had enough flexibility to accommodate that.”

Importance of recognition. It was very important to participants, and to mentors in particular, that their department Chairs receive comprehensive information on their involvement in P2P, particularly the time involved, at the beginning of the program. CTSI sent out a letter to all participants and Chairs upon acceptance into the program, outlining the commitment to P2P. “I really appreciate the letter of participation that came through.”

The value of structure to the program. The value of being in a formal, structured program was mentioned as supporting participation and validity.

“I think there was a real advantage to the fact that we were in a formal mentorship project that gave it some credence…”

“It was a formalized learning piece for me.”

“It was really good to have a framework.”

Length and layout of the program. The length of the program was debated somewhat but the current timing – the first workshop beginning before a term, and the layout of the three workshops plus meetings, was approved by the majority. Many suggested that partners meet before the first workshop or that the first workshop provide more time for partners to get to know one another. Some people would have liked a longer program, others found the format just right.

Resources and Activities

The mentor-coach model: Effective and challenging. The mentor-coach model taught in Workshop #1 presented participants with specific strategies for listening and supporting one another. Some participants expressed struggle with this request. “I know we have been talking a lot about reciprocal relationships, but the idea of mentee/mentor/coach, is kind of a confusing thing.” This mutually reciprocal collaborative model was expected of these mentor-mentee relationships with no one person adopting an exclusive role of advisor or advisee. Participants grappled with this notion of reciprocity in the mentor-coach model and many mentees cited concern that they hadn’t reciprocated enough and were on the receiving end of what could be viewed as an inherently unequal relationship due to the differences in experience. These comments around contemplating the mentor-mentee relationship came up frequently, suggesting reflection on the partner dynamic and the challenge of moving from a model of “sage advisor” to a reciprocal “mentor-coach”.

“It’s a bit disingenuous almost to pretend it’s symmetric because I’ve been teaching for 24 years and a lot of things I’ve already tried, and it’s not that I couldn’t learn from him, but there was a lot of pressure in a way to come up with new things I hadn’t thought of before.”

“I think our relationship was very one-way.”

Possibly unbeknownst to mentees, mentors often expressed a rewarding experience, were learners in the process, and reported value and satisfaction in furthering their mentor-coach skills, renewed enthusiasm in teaching and in learning and expanding their own teaching knowledge.

“I’m starting to think a lot about my first classes now, having seen my partner teach her first class.”

“I was actually really taken by the research that my mentee was working on.”

Comments around contemplating the mentor-mentee relationship and communication came up frequently, suggesting valued reflection on the dynamic and a shift to a model of reciprocity. Other elements to the Workshop content were listening skills; many respondents reported finding those techniques useful. “For me it would be being a little more mindful about giving feedback and maybe not trying to jump in with all the solutions right away.” One participant described the first relationship and skills development workshop as problematic or “too flakey.” Another reported that the mentor in their pairing adhered closely to the “be mindful of always providing advice to your peer” sentiment and it created limitations on their conversation. Other participants reported utilizing elements from the workshop that worked for them, including flexing between advisory and more learning-focused and reflective moments, and went on to enjoy a successful reciprocal relationship.

Other resources and activities. The first workshop received mixed reviews and the accompanying published resource book (When Mentoring Meets Coaching), was generally disregarded. CTSI’s peer observation worksheet was very well received as was the Peer Observation of Teaching: Effective Practices guide. The mid-course evaluations workshop content in Workshop #2 was appreciated by some but the mid-course feedback tool Bluepulse was not attempted by most. The participant log, and reflection exercise were not mentioned much.

“The structure for the observations worked beautifully for us.”

“I did not like the book.” “I didn’t use the book.” “We didn’t use the book either.”

“We used the peer observation guideline, as well, which was great.”

“I was really happy that the workshops were focused and concrete.”

“I didn’t like some of the stuff in the first workshop… It was way too touchy feely.”

Many people referred to the value of learning about “listening through versus listening to” but a few found it inhibited their conversation.

Nature of the Relationship and Conversations

Successful relationships. The partnerships and mentor-coach conversations were largely highly successful.

“It seems like we all had a positive experience, so I think the mentors were selected very carefully….’I really want to make you better’ and I could see my mentor also having a good attitude about learning from me as well.”

Mentees, in particular, expressed gratitude for their involvement in the program and for the experience they had with their mentor. Most of the pairings worked very well and participants reported happy surprise about how much they had in common with a faculty member from a department or discipline that differed from their own.

“One of the most eye-opening things for me and these conversations was with how much we have in common even though we are in different departments and different faculties altogether.”

Occasionally the difference in discipline limited what one of the partners felt they could offer and this was notably felt in one pairing where the pair were not in the same stream.

In many instances the desire to meet other mentors or mentee pairs, or to meet the whole cohort, was raised. Several participants did connect with one another outside of the workshop time due to physical proximity. They enjoyed this and also referred sheepishly to their cohort as a “clique”.

Value of conversations. Participants repeatedly mentioned in focus groups the value of having conversations about teaching, of face-to-face interaction, of sharing thoughts and ideas and going “back and forth” or “bouncing ideas” off one another. They shared tips, exchanged strategies, and even content. “There was never a shortage of topics.” Their conversations included philosophical ponderings and concrete “nuts and bolts” elements and pragmatic implementation methods or procedures including strategies for large classrooms, active learning and online learning. “We have actually been sharing exam questions, slides and articles.”

Safe space. There was a strong sense that there was enough trust established in these new relationships to forge a safe space for sharing uncertainties as well as enthusiasm about exchanging strategies.

“I found that this experience helped me to have a more positive sense of myself as an effective teacher – balancing some of the student evaluations of teaching that you get, which can be brutal. So, it was kind of…the less I felt like an imposter and the more I reconnected with myself as a competent, effective, capable teacher. I believe that benefitted the students …Work in academia can be very hard and you may not have the institutional, division or departmental supports that you wish you had.”

“Yes! In one of our Second Cup conversations we asked each other: ‘So, what’s the most brutal teaching evaluation you’ve received?’”

“It was just really nice to have somebody sort of just personally supporting you without judgement.”

Career development. Mentees did want to receive career advice and guidance and were

concerned about career development, performance, recognition and their dossier development. For such issues, they were seeking a more traditional mentor-mentee conversation.

“I’m the elder partner and she is pre-tenure, and it’s more of that career advice and navigating departmental relationships and teaching dossiers and things like that which was really career advice things that she came to me for and I’m happy to do that.”

This participant also explained how in addition to this element to the relationship they would discuss assignments and strategies and brainstorm in a way that was “much more mutual” as well. Course evaluation conversations evolved into career development conversations. Network expansion was also cited as of value and an asset when it was experienced as a result of the pairing.

Extension: Participants spontaneously raised recognition of the value of elements of the P2P program for their own departments or their own students, in particular graduate students. They wanted to share what they had learned, practiced and experienced with others.

“I think we will link our classes together at times as a result of this experience.”

“We were discussing ways we could bring this forward to our department.”

“I applied the P2P methods to my graduate students”

“It’s great to roll out to our departments, and have opportunity for really great resources and to more explicitly create mentorship models in our departments.”

Significantly, many were also interested in taking on a role in future P2P programming.

Summary

These research findings generally describe the P2P program as highly effective with a good basic structure that could continue to benefit from the ongoing use of specific resources and design features, along with a reconsideration of the use of certain resources, and modifications to the first Workshop. Overall, participants responded positively to the structure, format and timing of the program and reported an engaging, enriching experience. They pondered teaching strategies, mentorship, and professional skill development, in keeping with the goals of the program. The participants’ stated motivations for applying to the program were also satisfied (to connect with others, learn new strategies, benefit from career development and experience a mentor-mentee relationship). There was high satisfaction with the relationships and mentor-mentee meetings, and most intend to sustain their relationships. Many reported being interested in extending their new skills and program elements in their work or departments or being involved in the next iteration of the P2P program. A genuine enthusiasm for the program and the experience runs through the focus group transcripts and qualitative survey results.

The success of the program’s recommended resources varied, with the CTSI Peer Observation of Teaching: Effective Practices guide, Gathering Formative Feedback with Mid-Course Evaluations guide, receiving the best uptake, and the published resource book the least uptake. The workshops and program structure were appreciated. The activities to introduce the mentor-coaching model in Workshop #1 and Bluepulse in Workshop #2 were not as well received. Broad benefits of participation included learning, connecting and increasing skills and improved engagement. Mentees do want career development support and mentors valued the leadership and mentor-coach skill development opportunities. Participants would like more opportunities to meet other pairs or members of the cohort.

Participants found finding time to meet the greatest challenge, but it also came through that the significant time commitment provided meaningful rewards. Physical proximity was cited as a challenge in some cases. The absence of an active course in the term, illness, or inability to attend a workshop or meetings with their partner inhibited engagement or success in some cases. While rapport was cited by most as an enabler, an absence of rapport or “click” was a barrier to a richer experience for only one mentee.