Strategies for Using iClickers in Your Class

INTRODUCING CLICKER USE

As with any new instructional strategy, it’s important to explain to students why you have adopted this tool, how you expect them to use it, and how you expect it to contribute to the course and their learning. Some students may have used clickers before, but they will be new to many – especially first year students. Run a couple of test questions the first time you use clickers to make sure everyone is familiar and comfortable with the technology.

A video, produced by the Science Education Initiatives at UBC and University of Colorado, shares advice from experienced clicker instructors on introducing students to the technology:

ASKING QUESTIONS

A common mistake is to use clicker questions that are too easy. Students value challenging questions and learn more from them. Students often learn the most from a question that they get wrong. (From http://www.cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/files/Clicker_guide_CWSEI_CU-SEI.pdf, p. 2)

Clickers can be used to ask many different kinds of questions that assess different levels and types of learning. For example, you can:

- Assess student understanding with content-based questions. As you move through a presentation or lecture, pause at key points to check student understanding of essential concepts. Asking students to select the correct response to a multiple-choice question of material just covered provides them with an opportunity to review information, reinforces key ideas, and identifies to the instructor and the students whether the topic requires additional instruction.

- Ask students to apply or explore the implications of course content. Ask questions that require students to put information to work, perhaps in a slightly different context than the one in which the concept was initially explained. This supports students in understanding the material at a deeper level than memorization, and can help them identify which specific aspects of a concept or skill remain confusing. For example, you might explain an observable phenomenon, and ask students to select the hypothesis that best explains this outcome. The example below, (from Mathquest) represents a question based on the introduction of a basic mathematical concept (probability) within a social policy context: If the “One Family – One Son” policy were adopted, the average number of children per family would be? (Nearest answer)

a. 1.5 children

b. 2 children

c. 2.5 children

d. 3 children

e. 3.5 children

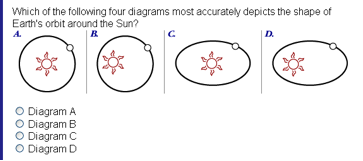

f. More Instructors who use in-class demonstrations or experiments also find it useful to ask students to predict the result of the procedure. This tests student understanding of the concepts that inform the demonstration or experiment, and links these ideas to what they are about to see. - Collect and challenge student pre-conceptions. Student preconceptions about a topic or concept can sometimes shape the way they take in new information. Asking students to identify their own pre-conceptions and showing them how they are shared or differ from those of their classmates can increase the chances that all students approach a topic from an informed perspective. Here is a (simple) example from the Science Education Resource Center at Carleton College:

- Help students identify fine but important distinctions. Beatty, Gerace, Leonard and Dufresne provide a description and example of this strategy, which they call an “Oops-go-back” question: Oops-go-back is an awareness-raising tactic involving a sequence of two related questions. The first is a trap: A question designed to draw students into making a common error or overlooking a significant consideration. The instructor allows students to respond and then moves to the second question without much discussion. The second causes students to realize their mistake on the first question. When students are “burned” this way by a mistake and discover it on their own, they are far more likely to learn from it than if they are merely warned about it in advance or informed that they have committed it. A simple example that is suitable early on during coverage of kinematics would be to ask students for the velocity of some object moving in the negative direction or in two dimensions, with positive scalar answer choices including the object’s speed, and also “None of the above.” Many students who are insufficiently attuned to the distinction between speed and velocity will erroneously select the speed. Then, a second question asks about the object’s speed, causing many students to consider how this question differs from the previous and realize their error. (From http://srri.umass.edu/files/beatty-2006deq.pdf)

- Provide a quick review of the previous class. At the beginning of the class, you might review the essential points of the previous lecture or other learning session to refresh students’ understanding and help them see the connection between topics.

- Get students ready for the following class or the next topic. Prepare students for their reading assignments or for the next lecture by having them respond to questions from material not yet covered. This will help alert them to essential information when they encounter it in their readings or lecture. Later, you can ask the same questions as review to have them demonstrate, and to demonstrate to them, what they have learned.

- Gather information about your students and their opinions and experiences. Especially on the first day or your first day using clickers, you might want to use some low-stakes questions that will help you learn about your students and help them to practice using the clickers. You might, for example, ask them to identify their year, their field of study, or their career ambitions. Throughout the course, you might continue to gather general personal views that particularly connect to the course material. For example, a class on ethics might ask students how they would respond to a particular scenario. Clickers can be useful for these kinds of questions as they offer partial anonymity: neither students nor instructors will be able to see on the histogram how individual students have responded to the question. However, if students have registered their clickers, instructors may have access to individuals’ responses – so, be cautious about asking very personal questions.

RESOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AND IDENTIFYING QUESTIONS:

The UBC Carl Wieman Science Education Institute provides the following tip for finding sample clicker questions online:

- The best way for finding online repositories of questions [in the sciences] is to type “ConcepTests” (the label chosen by Eric Mazur who developed this method of instruction) into Google. (From http://www.cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/files/Clicker_guide_CWSEI_CU-SEI.pdf, p. 10)

Burton, S.J., Sudweeks, R.R., Merrill, P.F., & Wood, B. “How to Prepare Better Multiple-Choice Test Items: Guidelines for University Faculty.” Brigham Young University Testing Services. Available online at http://testing.byu.edu/info/handbooks/betteritems.pdf

Beatty, I.D., Gerace, W.J., Leonard, W.J., & Dufresne, R.J. “Designing effective questions for classroom response system teaching.” American Journal of Physics 74(1). Available online at http://srri.umass.edu/files/beatty-2006deq.pdf